Section Ten - The complexity of life

A story about a seal , Ben Bernanke and a horse guru (3 minutes)

Understanding people

As we said before, a promise of (big) data is that it helps you understand people much better.

If you understand them better, you get indications of what drives them and you start to see patterns. That way you can serve people better as a customer, student, patient or citizen. As long as it is about suggestions for improvement, this can be fine. However, it becomes more questionable when impactful conclusions are drawn for an individual.

We have already learned that algorithms are opinions packaged in code and that data collections are far from neutral. That is a major problem if you use data to understand people. Even if you have good intentions you have to understand that reality is much more complex than thousands of data points.

This means people will get treated unfairly.

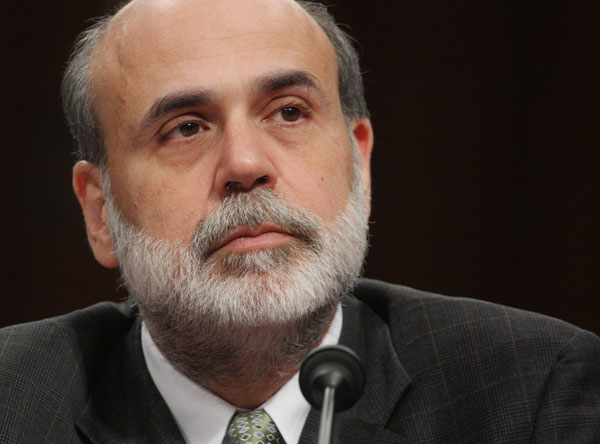

A seal & Ben Bernanke

We like to illustrate the statement above with a picture of a seal (below).

You recognized this picture as a picture of a seal, right? You have deduced that on the basis of a number of characteristics (bald, whiskers, sad look). And maybe you’re right, but are you sure? Are you really sure? Are you sure it’s not an image of a fur seal? Or a sea lion? You are – unless you’re a marine biologist – probably not really, really sure. And if you are still sure, you certainly do not know what the character of this seal is. Is it a penguin-hunting killer or a cozy seal who can juggle balls on his nose?

In part, (big) data does the same. A conclusion about something or someone is reached on the basis of a large number of characteristics. But no matter how sophisticated the (big) data technique is, it will never do justice to a much more complex reality.

An example: (big) data concludes that married men undoubtedly live healthier than single men. So, if you get a divorce, it would only be fair to pay more health insurance. Right? Maybe. But does the data know that you are divorcing a chain-smoking woman who is causing you stress, and frying burgers every day? Probably not.

Back to the seal.

Ben Bernanke, ex-boss of the Federal Reserve wanted to refinance his mortgage in 2014. That should not be a problem. Bernanke is bursting with money and he had a huge book deal at the time. However, he also just got a new job. As a result, the algorithm rejected his application. A new job? Risk! The algorithm looked at his baldness, whiskers and sad eyes and decided it was a seal.

Close, but wrong. Very wrong.

A million data points and Netflix

Maybe you now think: well, the problem probably is that we do not have enough data. If we had collected some more data then we would have known that Ben Bernanke is no seal. This is a common reflex.

Is there a problem with the data? Than we need more data.

However, remember the lesson from section two. Data is subjective. More data also means more subjective data.

Suppose Netflix tries to provide me with just the right tips for things I should watch at just the right time. They can collect all the data they want, but they only know what I watched on Netflix before. They do not have data on the things I wanted to watch. This way even with all the data in the world, Netflix still gives me tips based on the man I was, not the man I wanted to be.

From the history of Netflix. Read, but only if you want to.

In the beginning, you could create a waiting list on Netflix of films or series that you wanted to watch later. Only, it turned out that people hardly ever watched those movies or series. There was clearly a difference between what people wanted to watch and what they actually watched. People lied to themselves. So Netflix decided to look at what you were watching and what millions of others were watching and make recommendations based on that. That worked very well.

We know you better than you know yourself, Netflix said proudly. But was that really the case? I also know that there is a difference between the man I am and the man I would like to be. I don't need Netflix for that. The problem is, Netflix has understood that they can make more money from the man I am than the man I would like to be.

Unless they start reading my mind (this is also a bad idea, see crash course three).

A lesson from a horse gure

Jeff Seder is Harvard-educated horse guru who used lessons learned from a huge dataset to predict the best racehorses. He understood he had to use other data to find the best horses, so he created a device with which you can measure the size of the organs of horses. By cleverly finding the right proportions, he was able to predict which racing horses would win the most prizes.

But, in addition to all that data, he also relies on Patty Murray, a woman who loves horses more than people. She personally examines horses, seeing how they walk, checking for scars, interrogating their owners.

Together they pick the final horses they want to recommend. Murray sniffs out the problems that Seder's data, despite being the most innovative and important dataset ever collected on horses, still misses.

Big data does not mean we can throw data at any question. It does not eliminate the need for all the other ways humans have learned to understand the world.

They complement each other.

Take aways from section ten:

- Reality is much more complex than thousands/millions of data points;

- This can lead to unfair treatment of individuals;

- Data and old school understanding of the world complement each other.